Tata Imbroglio - Is Corporate Governance only a slogan?

Published: Dec 23, 2016

With demonetisation and the Tata war happening simultaneously, people are finding it difficult to prioritize their attention. Like the former, it has all the traits like element of suddenness, unexpectedness and future uncertainty. When Ratan Tata handed over the Baton to Cyrus Mistry, his golden words of advice were "be your own man". Little did Ratan Tata know that his advise would turn into a nightmare for the iconic Tata Group. On the fateful date of October 24, 2016, Cyrus Mistry was removed as the chairman of Tata Sons in an acrimonious manner almost akin to a boardroom coup. The reasons for his removal are still not known and remains mostly a matter of conjectures and speculation. Since then, there has been an avalanche of events and sub-events. On December 19, 2016, Cyrus Mistry finally stepped down from the board of all Tata companies, only to shift the board room battle to the courtroom with Mistry camp tolling the bell at the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) on grounds of oppression and mismanagement.

Quick recap of events

|

October 24, 2016 |

Board of Tata Sons ousts Cyrus Mistry as chairman; Ratan Tata appointed as interim chairman. |

|

Creation of Selection Committee to look for successor of Cyrus Mistry. |

|

|

Group Executive Council was immediately dissolved. |

|

|

October 25, 2016 |

First e-mail communication from Cyrus Mistry to Tata Sons directors. Cyrus Mistry lists out the challenges he faced acting as chairman and how his position was reduced to a "Lame Duck". |

|

November 1, 2016 |

Nirmalya Kumar who was a member of GEC steps down from the board of directors of Tata Chemicals. |

|

November 4, 2016 |

Indian Hotels Company Ltd. holds board meeting in which independent directors (including Nusli Wadia) support the leadership of Cyrus Mistry. |

|

November 10, 2016 |

Tata Son's Finance director Ishaat Hussain appointed as interim chairman of TCS. |

|

|

Tata Sons calls for Extra Ordinary General Meeting (EGM) of Indian Hotels Limited to remove Mistry as director. |

|

Tata Sons writes letter to shareholders explaining the reasons why it was not satisfied with the performance of Mistry. |

|

|

Independent directors supports leadership of Mistry. |

|

|

November 11, 2016 |

Tata Sons calls EGM of Tata Steel, Tata Motors and Tata Chemicals to remove Mistry as director and Nulsi Wadia as independent director. The reason given was that Mr. Wadia has been acting in concert with Mistry. |

|

|

Tata Chemical's director, Mr. Bhaskar Bhat resigns in protest when independent directors endorsed the leadership of Cyrus Mistry. |

|

November 15, 2016 |

Tata Motors independent directors issue a statement that all decisions taken by the company's board were unanimous and executed by the chairman and management. |

|

|

Mistry is removed as Chairman of Tata Global Beverages to be replaced with Harish Bhat. |

|

December 13, 2016 |

TCS convenes EGM. Cyrus Mistry removed as director of TCS. |

|

December 16, 2016 |

Nulsi Wadia files defamation suit in Bombay HC claiming damages of Rs 3,000 crore from Tatas for loss of reputation and credibility. |

|

December 19, 2016 |

Cyrus Mistry resigns from all Tata Cos. |

|

December 20, 2016 |

Cyrus Mistry and Shapoor Paloonji family files case before NCLT. |

|

December 22, 2016 |

Nusli Wadia removed as independent director from the board of Tata Steel. |

Two divided schools of thought have emerged ever since Mr. Mistry was removed from the position of chairman. The Tata loyalist group claim that Mr. Mistry was gradually hampering the conglomerate structure of Tata Group and did not function as per the ethos and values of the group. The Mistry group claims that Mr. Mistry was rationalizing the group and taking some harsh decisions to address the financial liabilities or legacy hotspots which he had inherited as chairman. We may or may not come to know the exact reason behind this blitzkrieg manner of removal, but there are certain broader concerns and takeaways for the Indian Inc and policy makers. This article will focus on such issues.

HOSTILE REMOVAL OF CHAIRMAN

The Companies Act, 2013 does not recognize the position of executive chairman, except for the position of chairman of board and shareholder meetings. Neither it lay down any procedure for removal of such executive chairman. So a company having such post, the appointment and removal is either governed by the Articles of Association (AoA) and the terms/contract of appointment. In this case, the AoA of Tata Sons lies in the eye of storm which have been amended several times in the recent past. The focus will be on Article 104B, 118 and 121.

The amended Article 104B confers special rights on Tata Trusts in nomination, appointment and removal of chairman i.e., it has rights to nominate directors comprising 1/3rd of Tata Sons board. Further, Article 104B states that any matter which requires majority of approval of the board of directors will also have to be approved by affirmative vote of nominee directors of Tata Trusts. However, the most crucial article is 118 which lays down the procedure for appointment of chairman.

Appointment of Chairman - Article 118

For the purpose of selecting a new chairman of the board of directors and so long as Tata Trusts has at least 40% shareholding, a selection committee shall be constituted as per the provisions of this Article to recommend the appointment of chairman of the board of directors, subject to Article 121 which requires the affirmative vote of all directors appointed pursuant to Article 104B. The same process shall be followed for the removal of the incumbent chairman.

Does it mean that a selection committee was required to be constituted even for removal of the chairman? As per the available facts, it does not suggest that the removal of Cyrus Mistry was recommended by the selection committee. Does it indicate that the removal was illegal as it did not comply with the AoA? If one has to play the role of devil's advocate, it can be argued that selection committee cannot be constituted when someone has to be removed. The role of selection committee ends as soon as the chairman is selected. Another possible interpretation could be that in case of removal of chairman, Article 118 is to be followed only in a limited manner (compliance of only Article 121) i.e., the approval of the majority of directors and affirmative votes of nominee directors of Tata Trusts have to be obtained.

Now taking up the issue that no prior notice was given to Cyrus Mistry, we need to look at the Secretarial Standards and Article 121B of AoA. As per the Secretarial Standards issued by the ICSI:

"The Agenda, setting out the business to be transacted at the Meeting, and Notes on Agenda shall be given to the Directors at least seven days before the date of the Meeting , unless the Articles prescribe a longer period."

Further, the Secretarial Standards provide:

"Supplementary Notes on any of the Agenda Items may be circulated at or prior to the Meeting but shall be taken up with the permission of the Chairman and with the consent of a majority of the Directors present in the Meeting , which shall include at least one Independent Director, if any."

It is not known whether removal of Cyrus Mistry was included in the board meeting agenda. Let's assume it was not mentioned, then the other possibility was to cover it as residual item. But then it is highly unlikely that any chairman would give his consent to discuss such agenda in the board meeting. In other words, it was not possible to comply with this requirement. However, Article 121B provides that if a director gives at least 15 days notice to the company or to the board regarding any matter for deliberation before the board, then the board shall take up that matter. The six directors who supported the ouster of Mistry could have served this notice and then it would have been compulsory for the board to take up the matter. But from the facts available in the public domain, it appears that this route was not adopted.

As the battle goes to the courtroom, the legality of the removal process of chairman in light of the AoA is likely to be challenged. Moreover, the position of chairman of a company is extremely crucial and with several family driven companies having this designation, there is a need for legislators to revisit the Companies Act. The present scheme does not have any procedure for appointment and removal of the executive chairman, let alone any need for disclosing reason for removal or right of representation. The impact of removal of chairman in Tatas is manifold like huge loss of market capitalisation, uncertainty among shareholders, jolt to the practice of corporate governance, unnecessary litigation and a vitiated atmosphere in the entire Tata Group. With express provisions and certainty in law, we can expect some transparency and avoid such hostile removals.

VULNERABLE INDEPENDENT DIRECTORS

The only silver lining in the Tata battle is that independent directors exercised their independence and taken stand against the controlling shareholders but, doing so has exposed their vulnerable position. When board of Tata Sons was using every possible strategy to oust Cyrus Mistry from the boards of other Tata companies, the independent directors of Indian Hotels supported the leadership of Cyrus Mistry based on his past performance. But the battle grew intense and ugly, when Nusli Wadia serving as an independent director on boards of several Tata companies opposed the removal of Cyrus Mistry. He was charged with the allegations of acting in concert with Cyrus Mistry. On December 22, 2016, Nusli Wadia was removed from the board of Tata Steel. Mr. Wadia has already filed a defamation suit (damages claimed Rs 3k crore) against Tatas in the Bombay High Court on the ground that his removal from the board of companies for no reasonable reasons affects his credibility and reputation. This is certainly a disturbing development which indicates the real position of independent directors i.e., either shape in line with the majority view or shape out.

Section 149 of the Companies Act read with Rule 5 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014 prescribes qualification for appointment of independent directors. Further, Schedule IV of the Companies Act lays down the code of conduct for independent directors. The Companies Act also prescribes strict liability if independent directors fail to act. However, the past two months have flagged the need for statutory protection of independent directors against the discretion of the non-independent directors in a situation of direct face-off. The question which arises is can an independent director be removed from the board of a listed company merely on the allegation of acting in concert with an ousted chairman ? Would supporting the leadership of an oust chairman based on his performance and economic considerations, mean acting against the interests of the company or shareholders? What are the specific grounds on which the board of Tata Sons is seeking removal of an independent director? The minority shareholders of Tata companies have already moved to the Bombay High Court challenging the provision in the Companies Act which allows voting by promoters in removal of independent directors.

Under the present scheme, an independent director can be removed under Section 169 of the Companies Act by merely passing an ordinary resolution. So the issue is can an independent director of a public listed company, who is supposed to represent the interests minority shareholders, be removed like any other regular director? The next obvious question arises can such promoters (representing Tata Trusts and Tata Sons) be allowed to vote on resolutions seeking removal of an independent director when their vested interest is more than obvious? Shouldn't the voting on such resolutions be restricted to only ordinary public shareholders?

These unanswered questions, make a strong case for immediate legislative interference in the Companies Act which does not carve out special grounds for removal of independent directors. In sum, if special role is expected from an independent director, special protection is warranted for such directors.

Appointment of TVS Motor chairman Venu Srinivasan and Piramal group chief Ajay Piramal as independent directors to the Tata Sons board has already been questioned with allegation that their appointment on the board of Tata Sons was done by the Tata Trusts to consolidate their control over the decision making powers of Tata Sons. Besides, K.B. Dadiseth, an independent director on the board of Indian Hotels, is also the member of Tata Trusts. Similarly, N.M. Munjee, an independent director on the board of Tata Chemicals, is also a trustee of Tata Trusts. Being a trustee on Tata Trusts, which is the majority shareholder of Tata Sons, the parent company of Tata Group operating firms, can by no means be equated with good corporate governance.

A survey done in 2015 reveals that 25% of independent directors on the board are either near or distant relatives. With the Tata episode and more statistical evidence in the background, the concept of independent directors having a definite ‘say' in the management of a company, seems a theoretical construct.

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE - A REALITY CHECK !

Unlike Section 169 of Companies Act, 2013, which gives right of representation to director before his or her removal, no such right is available to a chairman. So while statutorily there is no requirement of giving right of defence or citing reasons for removal of chairman, as a matter of good corporate governance, it should have been done. Removing the chairman of a company in this hostile fashion indicates a deep concern. The sudden sacking of Cyrus Mistry has been attributed to his non-performance. But did we have any quantitative yardstick to measure his performance? Were there any clear milestones set at the time of his appointment, which he was supposed to achieve within a stipulated period? If not, then in absence of any such tangible goals, removing him from on mere allegations is not only questionable but also sets a negative precedent for future appointments. If one reads the EGM notice the reasons for removal of Cyrus Mistry it only says that the board of Tata Sons has lost confidence in him and his removal was absolute necessary for the future success of the Tata Group.

Was it not a fiduciary duty of the directors of Tata Sons to clearly convey the reason to shareholders when its domino effect is visible on the listed companies, minority shareholders, investors and community at large? This compels us to question the statutory need for disclosure by the board of directors of a private limited company which in turn controls multiple listed companies? Tata Sons is managed by an exceptionally professional board, but if one looks at the AoA, it is clear that most of the issues requires affirmative vote of nominee directors of Tata Trusts. This requirement is in addition to the approval of majority of the directors. This in effect shifts the balance of decision making in favour of the Tata Trusts and dilutes the powers of the board of directors (refer Article 121A of Tata Sons). This also raises a question whether such article restricting the powers of the board is incongruous to the provisions of Companies Act?

|

Type of Voters |

Vote for |

Vote against |

|

Promoter |

100% |

None |

|

Institutional |

57.46% |

42.54% |

|

Public |

22% |

78% |

Cyrus Mistry was removed as director of TCS with the majority of shareholders' approval. But if one looks at the composition of voting in the EGM, it would reflect that the minority shareholders did not support the resolution of removal. The resolution could be carried out successfully only with the overwhelming majority of promoter shareholders. While legally this is correct, but claims like Tatas stands for protection of minority shareholders and upholds corporate democracy cannot be taken any longer at its face value.

With the matter now going to the NCLT and allegations like impropriety in deals like Air-Asia, more instances of non-adherence to corporate governance is likely to surface.

CONGLOMERATE STRUCTURE - LESSONS FOR TATAS AND OTHERS

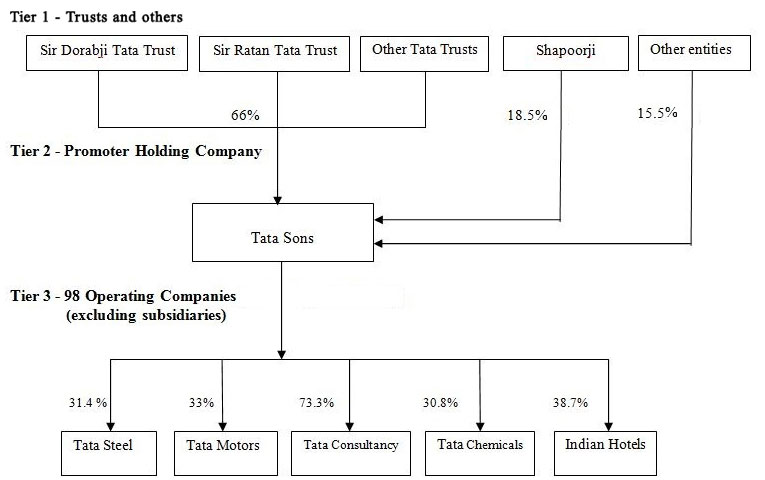

The Tata Group operates in a conglomerate structure which is common in emerging markets like India. It is a three tier architecture with trusts controlling the holding company (Tata Sons) and Tata Industries which inturn controls operating companies spread across seven industries. Several research shows that conglomerate structure provides easier access to capital and foreign investors find it more reliable because solvent conglomerate stands as surety for their group firms.

Tata's Conglomerate Structure (% of shareholding is approximate)

The allegation against Cyrus Mistry was that he tried to dilute the conglomerate structure by diluting the representation of Tata Sons on the board of different companies. Mistry operated through the Group Executive Council which is said to have gained more power than the board of Tata Sons. It was also alleged that Mistry tried to write off the losses instead of working on strategies to turnaround the ventures. But the legacy Mistry inherited when Ratan Tata stepped down, is known to the whole world. So if Mistry found it fit to dispose of the bleeding assets instead of carrying them as financial burden, this could at best be construed as strategy not acceptable to Tatas, but not non-performance.

Conglomerate structures in India are characterized by concentration of powers. Tata Sons operated under the direction of Tata Trusts where a member of the Tata Trusts has always been appointed as chairman of Tata Sons to keep the link between Tata Trusts and Tata Sons strong and effective. This was the first instance where a non-member of Tata Trusts was appointed as the chairman of Tata Sons. But this created dual centre of powers where Tata Trusts was controlled by Ratan Tata and Tata Sons was driven by Cyrus Mistry. Soon this asymmetry in power equation created disconnect, which snowballed into an avalanche. Had Mistry been a mere professional chairman, he would have had two options, either resign or toe the line. But Mistry family owning 18.4% equity shares in Tata Sons, he refused to exit without putting up a fight.

This failed experimentation has not only impacted the Tata Group but will also serve as key lesson for other family owned conglomerates. Going forward, Tata would restore the old structure and likely to place common directors across all Tata Companies so the link between Tata Trusts through Tata Sons and Tata Cos remains strong and effective. Further, companies would be best advised to have well defined deliverables for future professional chairman or similar key positions to ensure clarity and quantifiable performance. Also, a clear cut dispute resolution process incase of divided opinions would avoid such bad blood.

CONCLUSION

The initial euphoria of new Companies Act and better corporate governance has finally settled down and the cracks in the system are again visible. Tatas have been known for its institution value and responsible capitalism. But this event has once again exposed the reality of institution giving way to individuals and governance taking back seat. Some experts forecast that the legal battle is poised in favour of Tatas but the perception of brand Tata has taken a long term beating.

The other revelation is that India Inc is still not prepared for professional chairman in family owned conglomerates, especially when promoters even though retired, cannot let go the driving seat. The professional chairman or CEO enjoys their office as long as they enjoy the trust of promoters. This position is quite similar to the relationship between bureaucrats and ministers. As far as the outcome of ongoing legal battle is concerned, it would be sad if this event is reduced to lawyers delight or a dream case-study for business schools. Instead, the outcome should instigate changes in the existing statutes and compel business houses to introspect and reverse this steadily falling graph of corporate governance. The creation of dual power centre must be avoided and roles, responsibilities of professional CEOs must be codified to gauge performance in tangible terms. The removal of Nusli Wadia as independent director, although with the consent of shareholders, is not expected to set a positive precedent on the institution of independent directors, unless we take a re-look at the extant provisions of the Companies Act.

Lastly but most importantly, the need for strict disclosures and transparency norms has been acutely felt at the level of promoter holding company, especially when its decisions directly impact the listed operating companies. The mere status of private limited of such promoter company should not be allowed to shield it from scrutiny by authorities and shareholders at large.